Acquired inheritence

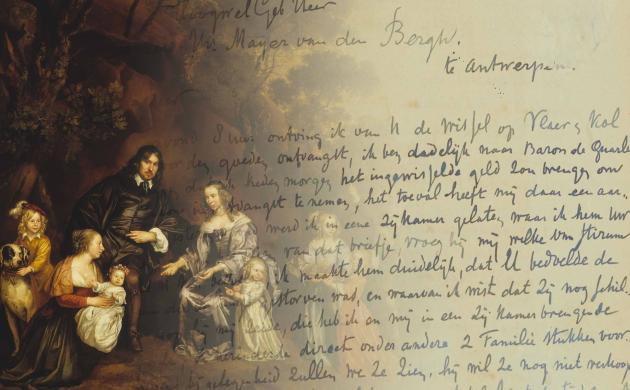

In 1897, Fritz purchased no fewer than 18 family portraits. Six of them, including that of Meyndert Sonck and his family, came from the estate of the Bredehoff family. The Bredehoff family was not raised to the peerage until the 19th century, but by then had belonged to the Dutch patriciate for centuries. They were a prominent family in Hoorn and North Holland. In the archives, we read that François van Bredehoff Esq. did not initially inform his sister Elisabeth about the sale of the family portraits because he was afraid that she would find the loss too painful. Only when the paintings were retrieved from her home did Elisabeth learn that they had been sold.

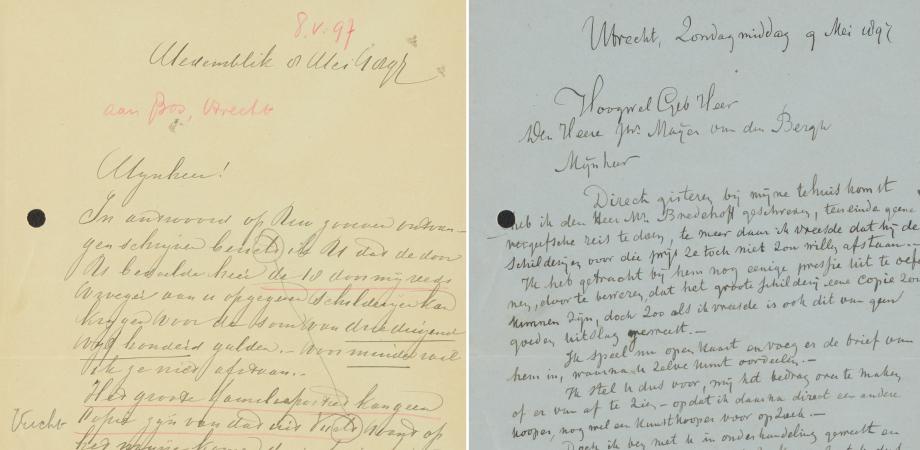

Left: letter from François van Bredehoff to Jan Bos about the family portraits, 08-05-1897 (MMB.A.0765). Right: letter from Jan Bos to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh about family portraits, 09-05-1897 (MMB.A.0765).

Letter from Jan Bos to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh about family portraits, 14-05-1897 (MMB.A.0768).

Jan Albertsz. Rotius, ‘Meyndert Sonck and his family’, 1662, MMB.0138.

From this correspondence, we can see how important the portraits were to the Bredehoff family and how strongly they were linked to their identity. Fritz, who obviously did not have that feeling seems, at first glance, to be primarily interested in the artistic value of the paintings. In his letters to Jan Bos, who bought the works for him as an intermediary, he speculates about the painters. Bos himself calls Meyndert Sonck and his family "particularly beautiful." Yet the portraits also have additional meaning for Fritz because of their connection to historical figures. Those portrayed were important political figures in Dutch history. For example, Meyndert Sonck was a high-ranking administrator at the Dutch East India Company.

Left: van Miereveld Studio (Michel Jansz. van Miereveld), Paulus Cornelisz. van Beresteyn, 1612-1649, MMB.1599. Right: van Miereveld Studio (Michel Jansz. van Miereveld), Paulus Cornelisz. van Beresteyn, 1612, MMB.0122.

Status symbols

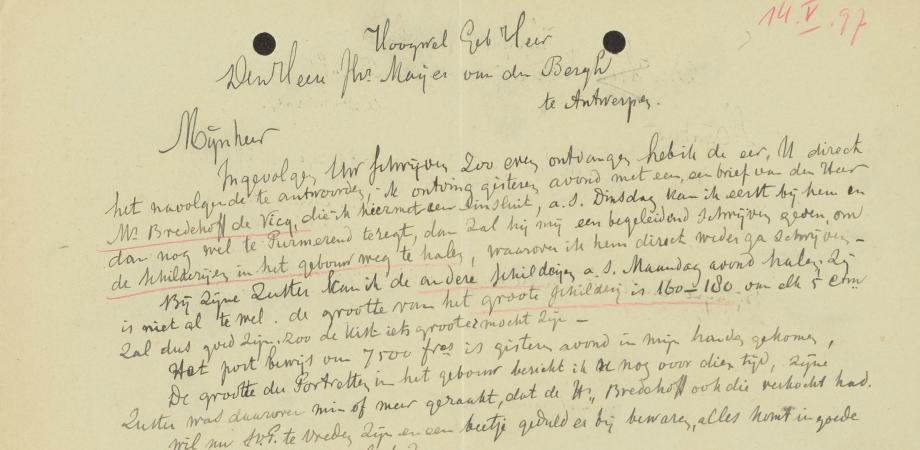

Also in 1897, Fritz purchased a collection of 17th-century portraits of the noble Beresteyn family. The politician Paulus van Beresteyn and his wife Volckera had their portraits painted in 1612 and then had these portraits copied to give to all their children. In such a case, the artistic qualities of the artists hardly mattered; the works were made primarily in memory of those portrayed and to serve as status symbols for the descendants of Paulus and Volckera. The works were purchased in Utrecht, directly from the Beresteyn family. Fritz's purchase of these paintings is certainly notable and seems to indicate an interest in the people painted, more than in the paintings themselves.

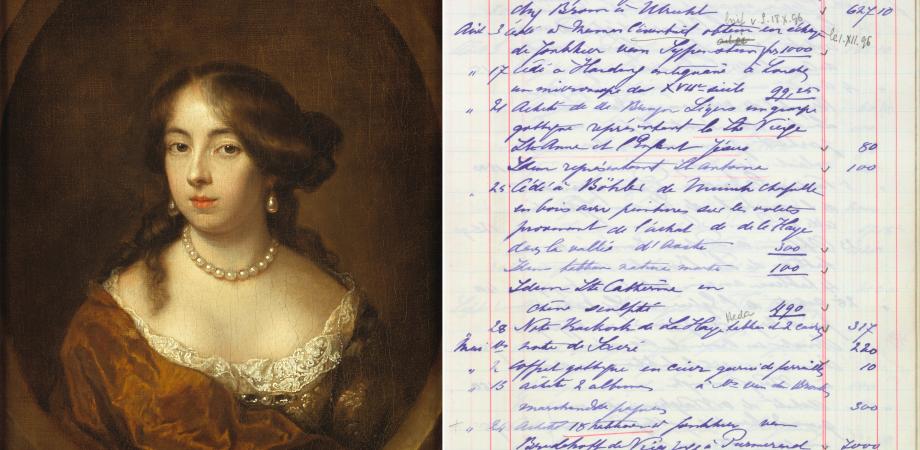

Left: Caspar Netscher, ‘Cecilia de jonge van Ellemeet’, 1679, MMB.0160. Right: page from Fritz's purchase ledger, which also mentions the purchase of the Bredehoff works (MMB.A.2500).

The Beresteyn family was connected to the Bredehoff family. Cecilia van Ellemeet was a daughter-in-law in the Bredehoff family and a great-granddaughter of Paulus Cornelis Beresteyn. Fritz was aware of this. In fact, it seems to have been part of his motivation to buy both collections. This raises questions: why was Fritz so interested in portraits that were not of his own family? Was it purely out of historical interest? Or did he find it appropriate to collect portraits of important families from Flanders or the Netherlands after he himself was raised to the nobility in 1888?

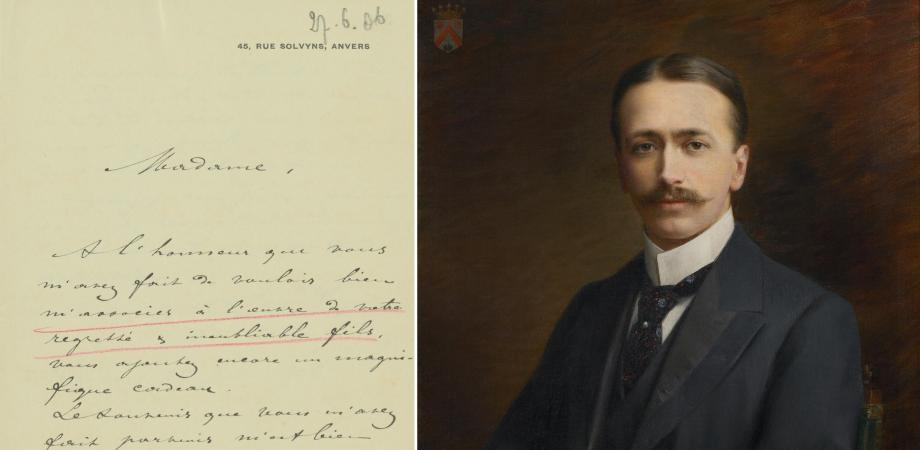

Left: letter from Jozef Janssens de Varebeke to Henriette Mayer van den Bergh, about a visit to her museum, 27-06-1906 (MMB.A.1609). Right: Jozef Janssens de Varebeke, ‘Portrait of Fritz Mayer van den Bergh’, 1901, MMB.1871.2.

Immortalised in their museum

Portraits of Fritz and Henriette themselves also hang in the museum. Henriette commissioned the portrait of Fritz after he had already died. It was painted by Jozef Janssens de Varebeke, a close friend of Fritz's who served on the museum's board for a time after the latter's death. The choice of this portraitist must therefore have had great personal value for Henriette and, moreover, Janssens de Varebeke was highly regarded as a painter of the Catholic elite in Antwerp. By hanging Fritz's portrait in the museum, Henriette placed it on the same level as the other portraits in the collection. Fritz and Henriette are thus also immortalised as historical figures.