Anonymous, 'Portrait of a lady' (after Antonio del Pollaiolo), 16th century (?). MMB.1069.

Antonio del Pollaiolo, 'Portrait of a Lady', c. 1470-1475. Milan, Museo Poldi Pezzoli, inv. no. 442.

© Lombardia Beni Culturali

Question marks and Italian connections

One of the most notable drawings that Fritz purchased is a pen drawing in brown ink, about 10 by 15 centimetres. The lady depicted very much resembles a portrait by the late-15th-century Florentine artist Antonio del Pollaiolo, which is in the Museo Poldi Pezzoli in Milan. The rest of the story is a string of question marks. Who made the drawing and when? How did it end up in Fritz's collection? As a seasoned art expert, did he suspect that the work had more symbolic than financial value, and was it more of a purchase 'for pleasure'? Or did he just consider the work a full part of his collection, out of his love for Italian Renaissance art?

By the early 1890s, Fritz's connections with art dealers and experts reached as far away as Italy. He maintained contacts with small antique dealers around Como, Bergamo, Milan and Brescia, as well as notorious art experts from Florence. To view potentially interesting purchases in-situ, he usually sent intermediaries – including his conservator Joseph Delehaye – but in 1890, he himself undertook a trip to Italy. In the extensive correspondence archives, we find, among other things, advice from the art historian Giovanni Magherini Graziani (1852-1924) on some interesting acquisitions for Fritz's collection, and also from the renowned Florentine art dealer Stefano Bardini (1836-1922). You will read more about him in a moment.

Too tight a budget for Italians

Oddly enough, Fritz's interest in the Italian market mainly focused on works by artists from the Low Countries. As a foreign collector, hunting Italian art objects in the late 19th century was indeed no mean feat. After increasing criticism of the mass export of artworks, transferring heritage objects abroad was only allowed after an officially approved request to the government. Those who ventured into illegal exports risked fines of up to 100,000 lira. But export legislation and enforcement were hardly on top of their game. Many masterpieces still disappeared under double floors in a ship's cargo hold, or were even hidden behind a mirror or under a tabletop. In 1881, for example, the aforementioned Stefano Bardini managed to detach some Botticelli frescoes from the wall of a Florentine villa and smuggle them to the Louvre, after his official export request was denied. One fragment was seriously damaged in the process.

An even greater obstacle to Fritz's eventual pursuit of Italian Renaissance masters was undoubtedly his budget, which was too tight to participate in the rush for 15th and 16th-century works at the time. These were not only the highlight of the canon in the late 19th century thanks to a great deal of academic research on them – for private collectors they were above all a means to glorify their status: it was as though they were following directly in the footsteps of the Medici. Competition among national museums within Europe and among American private collectors drove prices to astronomical heights. In some letters in Fritz's archives, dealers recommend to him some great names such as Rafael, Bellini and Pinturicchio. But with his mid-size budget, he could only dream of having such masterpieces in his collection.

Alternatives: underexposed periods and drawings

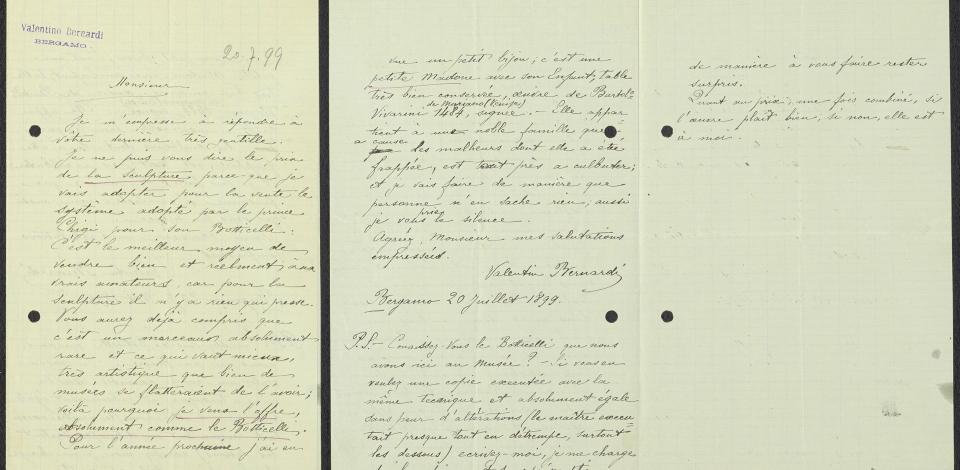

19th-century collectors who could not afford original masterpieces could, as a consolation prize, have a faithful copy produced in a painter's studio. Fritz got this suggestion from painter-restorer Valentino Bernardi, who had plans to recreate a Botticelli 'with the same technique, absolutely identical with no risk of alterations'. An authentic Botticelli went under the hammer at the Paris auction house Trotti in 1907 for 200,000 francs – a huge sum...

Letter from Valentino Bernardi to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh, 20-07-1899, MMB.A.0959.

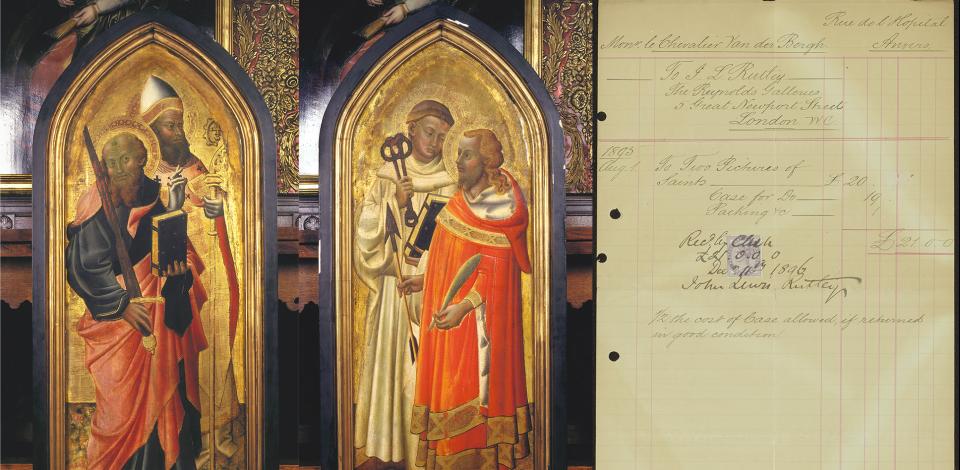

As a discerning collector who valued authenticity, Fritz may have shown little enthusiasm for contemporary copies. Fortunately, his art history interests were broad enough to find sufficient alternatives to Italian Renaissance paintings and sculptures. He therefore invested in Italian works from then somewhat underexposed historical periods. Moreover, by looking for those objects at French, German and British auctions, he circumvented the risks of clandestine export. For example, he took an interest in Tuscan masters of the 13th and 14th centuries, somewhat ahead of trends in the art market. From the London antique dealer John Lewis Rutley, he bought two 14th-century retable panels from Siena in 1895 for the surprisingly low price of 532 francs. 18th-century works from Italy also appealed to Fritz: in the same year, a grisaille painting by Creti, Ferraiuoli and Paltronieri cost him only 250 francs at Christie's.

Angelo di Puccinelli (late 14th century), 'Retable panels with Pope and Holy Bishop (left) and Leonardus and Sebastian (right)', MMB.0196 and MMB.0197. / Bill from John Lewis Rutley for the purchase of these panels in August 1895, 12-11-1896, MMB.A.0722.

Donato Creti, Nunzio Ferrajuoli and Pietro Paltronieri, 'Allegorical Tomb of Joseph Addison,' 18th century. MMB.0171.

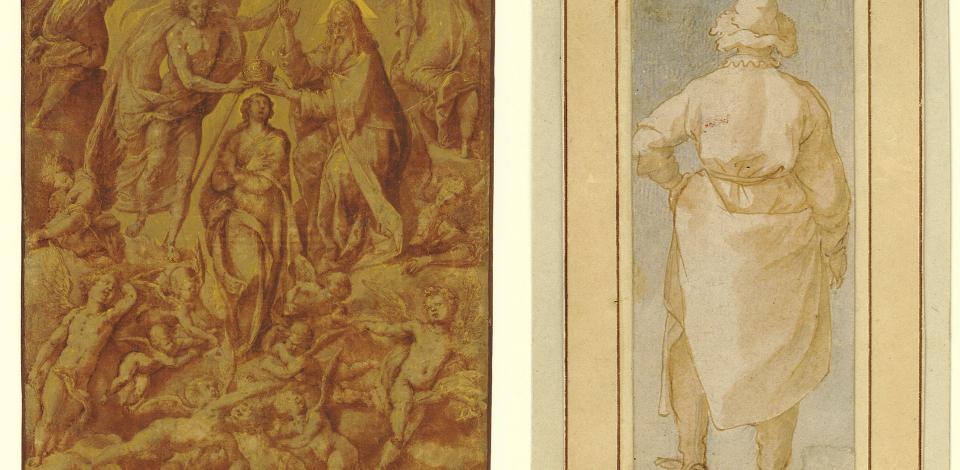

Second, Fritz also turned his attention to Italian Renaissance and Baroque art, but in that case he opted more often for drawings: he deliberately sought out auctions by foreign private collectors who specialised in drawings, prints and watercolours. In 1895, he acquired a Coronation of the Virgin in Munich for the price of 70 francs. Fritz's intuition that this was an authentic masterpiece was correct: recent research attributed the work to Jacopo Ligozzi (1547-1627). Some while later, he bought a Day Labourer seen from behind at an auction in Cologne for only 35 francs, then attributed to Titian.

Jacopo Ligozzi, 'Coronation of the Virgin’, 1600-1619. MMB.1041 / Anonymous, 'Day labourer seen from behind', MMB.1068.

Self-profiling

As to the exact story behind the Pollaiolo drawing and why Fritz acquired it, we are left to guess. According to the very oldest museum inventory, it is a 16th-century copy by an anonymous admirer of Pollaiolo. Did Fritz see it as a substitute for the Renaissance paintings he could not afford? On his trip to Italy, did he visit the Poldi Pezzoli collection, where the original portrait was to be found, and was this drawing a souvenir for him? In any case, it is a perfect fit for the self-profiling Fritz had in mind with his collection, as a lover of the Renaissance and the portrait genre. And as a collector of drawings.