Art and Knowledge

Wilhelm Bode (1848-1929) and Max J. Friedländer (1867-1958) both worked at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. Bode became director there in 1890 and then hired Friedländer as an assistant for the paintings department. Under Bode and Friedländer, the Berlin museums evolved into some of the most important museums in Germany.

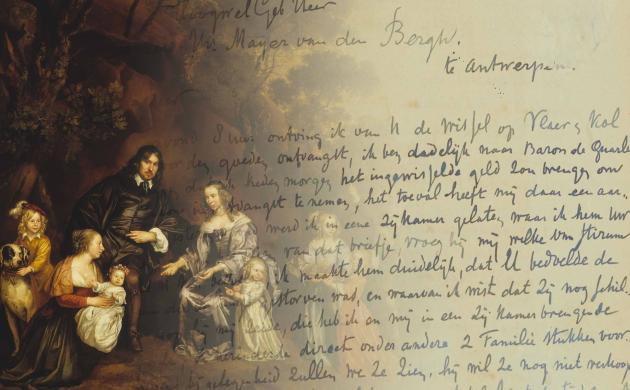

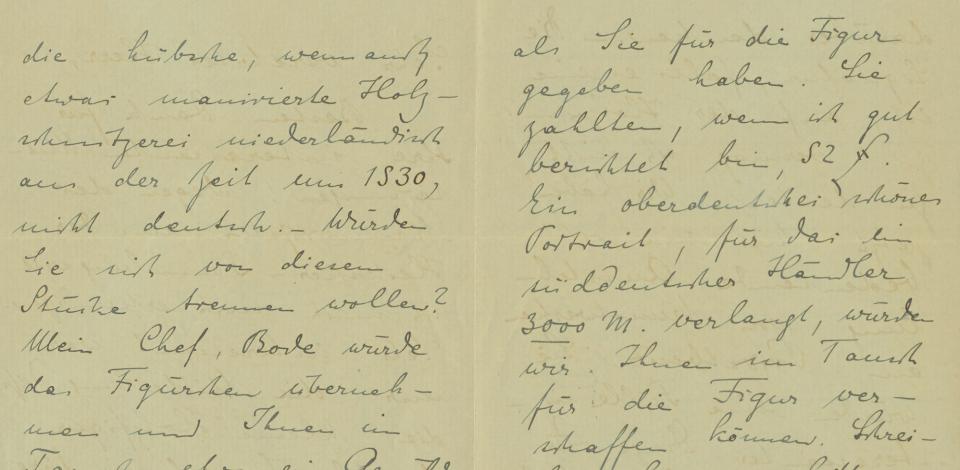

Letter from Wilhelm Bode to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh, about works of art Fritz might be interested in, 29-11-1899 (MMB.A.1006).

Left: Rudolf Schulte im Hofe, 'Portrait of Max J. Friedländer', 1907, 93 x 72 cm. Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe (CC0). Right: Max Liebermann, 'Portrait of Wilhelm Bode', 1904, 114 x 92 cm. Alte Nationalgalerie Berlin (CC0).

Bode and Friedländer were both connoisseurs. The term 'connoisseur' refers to researchers who attribute works of art to particular periods or artists based on their stylistic characteristics. These attributions are based on experience with and knowledge of a particular artist or art movement. They are also determined by the connoisseur's 'instinct'. "Ultimately, our decisions rest on something we cannot name," Friedländer wrote of his connoisseurship.

Nowadays, with numerous new high-tech techniques, connoisseurship is sometimes criticised for its subjective nature, which could lead to unreliable attributions. Indeed, Bode was later found to have made some major mistakes - for instance, he once attributed a 19th-century statue to Leonardo da Vinci. In the art market around 1900, however, many works did not yet have a clear history or provenance and technical means of research were still very limited. The attributions by experienced connoisseurs were therefore of great importance.

Expert opinions

Fritz met Friedländer in 1894. The art historian was then only 27 years old and working as an assistant at the Cologne Wallraf-Richartz-Museum. Through Friedländer, Fritz got to know Bode. The advice of these art historians was hugely important for Fritz, who had no formal education in art history. He regularly sent them pictures and invited them to come and see his collection.

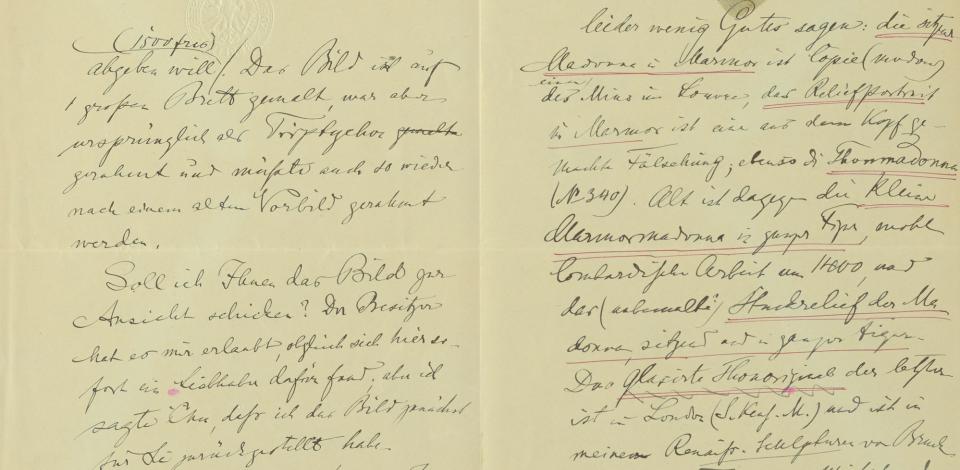

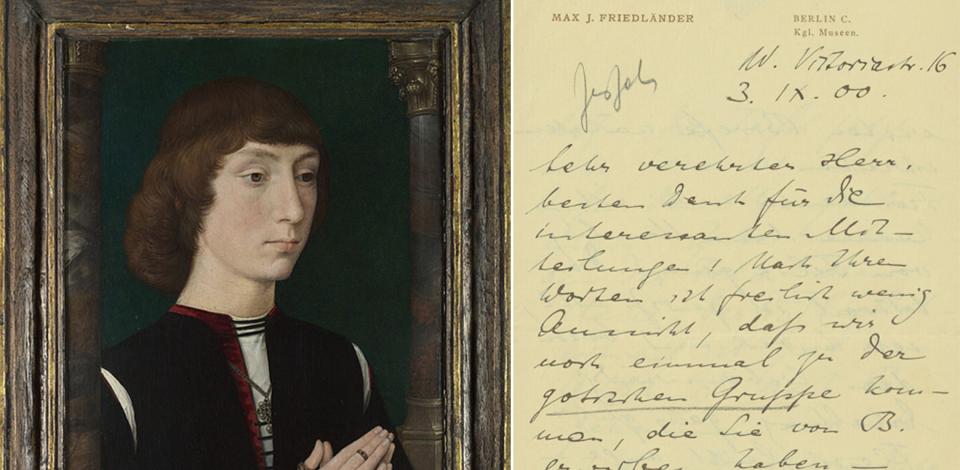

Left: Hans Memling, 'A Young Man at Prayer', 1470s, The National Gallery, London (© National Gallery). Letter from Max J. Friedländer to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh about this portrait, 03-09-1900 (MMB.A.1098).

Letter from Max J. Friedländer to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh about this portrait, 03-09-1900 (MMB.A.1098).

The archives contain dozens of letters in which Friedländer and Bode offer their advice on artworks Fritz had bought or was considering to buy. They did not shy away from giving him negative advice. For example, Friedländer once wrote of a Flemish triptych, "If I were you, I would just leave it at the photograph." The art historians also wrote to Fritz when they came across works they thought might interest him. Friedländer recommended to Fritz, for example, A Young Man at Prayer by Hans Memling, from the collection of the German Eugen Felix. According to the art historian, the painting was in perfect condition, but probably not cheap. Presumably, the price was indeed too high for Fritz as the work now hangs in the National Gallery in London.

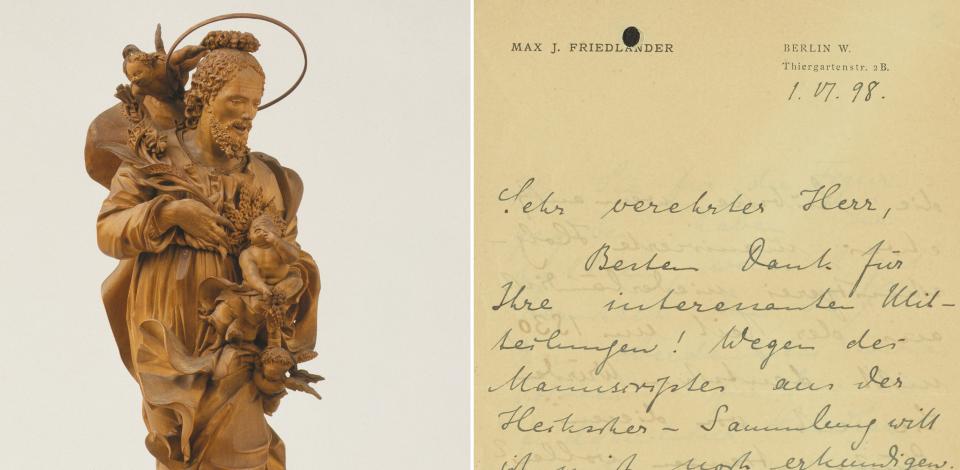

Bode also helped Fritz with the attributions of sculptures he had purchased. When Fritz sent him a photograph of a Saint Joseph with child, Bode was so impressed that he offered to exchange the work for a portrait that he felt had much greater market value. Fritz did not accept his offer and the Saint Joseph is still on display at the museum today.

Left: Master of I.M.HP, ‘Saint Joseph with Child’, mid-17th century, MMB.0218. Right: letter from Max J. Friedländer to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh regarding Bode's offer to exchange the 'Saint Joseph' for a portrait, 01-06-1898 (MMB.A.0856).

Letter from Max J. Friedländer to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh regarding Bode's offer to exchange the ‘Saint Joseph’ for a portrait, 01-06-1898 (MMB.A.0856).

A headstrong amateur

Although Bode and Friedländer were regarded as two of the foremost art historians in their field in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Fritz never blindly followed their advice. The preserved correspondence shows that he rarely chose to buy the works offered to him by Friedländer or Bode, for example. He primarily listened to the negative advice of these art historians; if they advised him against a work, he did not buy it. Fritz was a discerning collector who used set criteria for the works he wanted to include in his collection. He built his collection with the limited resources at his disposal and could not always afford expensive works of art. He also did a great deal of research on his own collection. He would have valued the advice of experts such as Bode and Friedländer in his research but, at the same time, profiled himself as an independent and critical collector who ultimately made his own choices.