Women and museums

Nearly half of the collectors’ museums existing in Europe and North America were founded by women. Good examples are the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston or Helene Kröller-Müller in the Dutch town of Otterlo. This is striking because women did not have a particularly strong position in the art world around 1900. Women had limited access to training or employment within the arts. In Belgium, moreover, married women had little control over their own money until the mid-20th century, which made it difficult for them to purchase art without their partners' permission.

Women were, however, expected to engage in art privately. For instance, drawing and music lessons were a regular part of girls' education. Married women were expected to take care of the interiors of their homes. Displaying works of art was a common part of this in wealthy families.

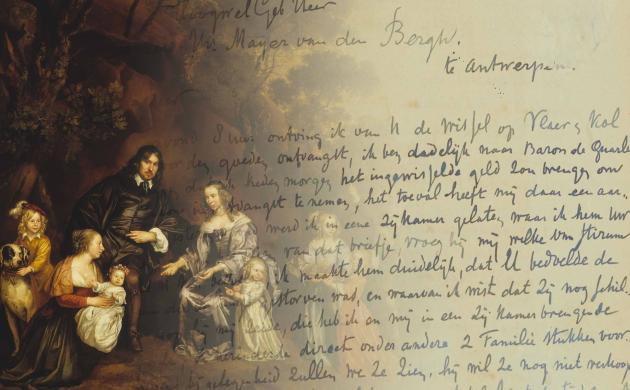

Letter from Louise de Hem to Henriette Mayer van den Bergh about the foundation of the museum, 05-02-1905 (MMB.A.2132).

The transition from an interior filled with works of art to a real collector's museum proved, in some cases, to be smaller than expected. Collectors' museums were often arranged as a series of 'period rooms' with interiors from different historical periods. They were much more intimate and homely than national or civic museums. The domestic character and connection to designing interiors meant that the collector's museum was seen as more appropriate for women. That role, in turn, justified the 'public' function that the museum founder assumed.

A shared passion

After her marriage to Emil, it was Henriette who engaged in art and culture, while her husband focused primarily on the family business. For example, we know that in 1877 Henriette lent some of the family's artworks to an exhibition organised in Antwerp to celebrate the three-hundredth birthday of Peter Paul Rubens. In addition, she collected letters and autographs of important European artists at an early age. Some of these belong to the museum archives (and have been digitised).

As Fritz turned to collecting at the beginning of 1880, the love of art formed a shared passion between mother and son. Although few letters have survived from Henriette from the period when Fritz was building his collection, the archives do show that she influenced his activities as a collector. She regularly paid bills for her son or they attended auctions together. In 1898, Fritz purchased the entire collection of Carlo Micheli in Paris, which was a crucial moment in the building of his collection. However, this purchase was only possible because Henriette lent him some of the money.

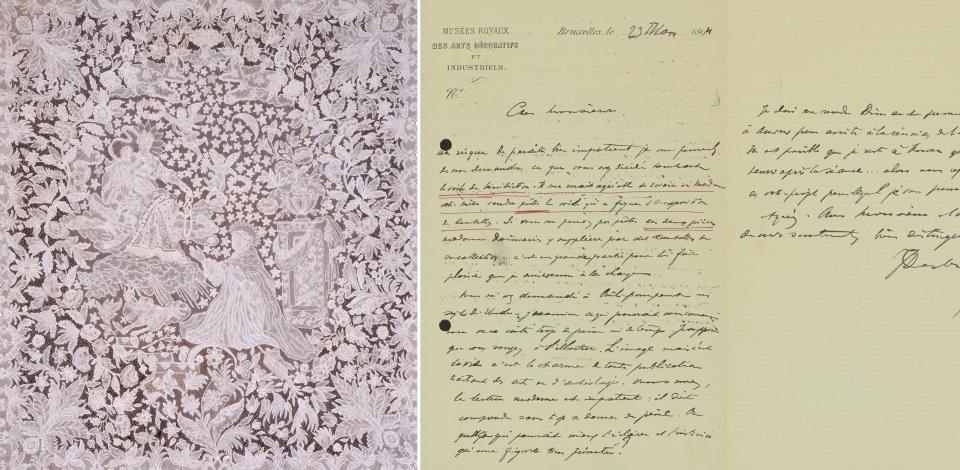

Left: anonymous, Benediction velum in Brabant bobbin lace, 1700-1720, MMB.1488. Right: letter from Joseph Destrée to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh with questions about Henriette's lace works, 23-03-1894 (MMB.A.0422).

Henriette supported her son's activities and, in turn, he took her tastes into account in his art purchases. Henriette, for example, had a penchant for lace, an art form that was especially popular with women in the 19th century. Fritz regularly bought lace pieces for his mother, which he noted in his purchase book. That they were purchased for Henriette becomes obvious from a letter Fritz received in 1894 in which Joseph Destrée, curator of the Brussels Museum of Decorative Arts, asks if Henriette would like to lend her lace works to an exhibition. These works were eventually included in the museum collection.

A personal museum

Just a few months after Fritz's death on 4 May 1901, Henriette began to plan the foundation of the museum. Fritz, too, may have built his collection with the idea of one day establishing a museum, but that idea was far from concrete at the time of his death. Henriette had the museum designed around the objects already present in the collection. She integrated the furniture, fireplaces and stained glass windows that Fritz had collected into the architecture of the building. As such, she aimed to honour the memory of her son.

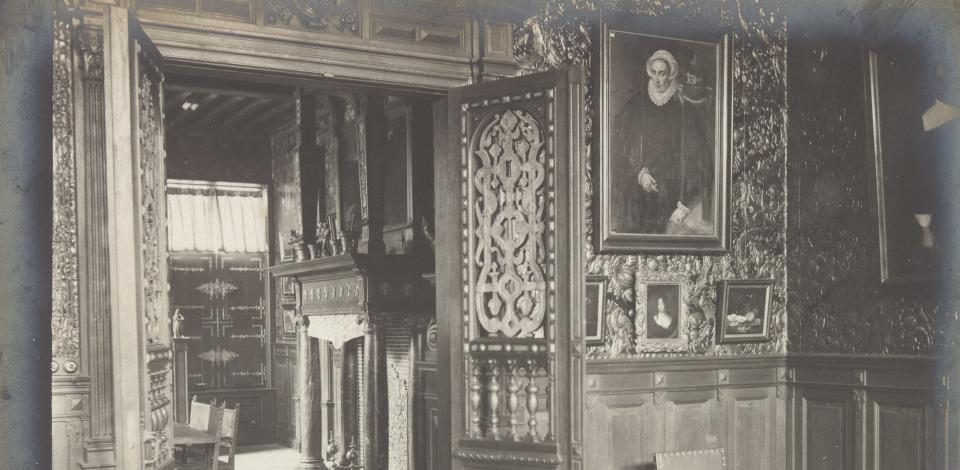

Early 20th-century photograph of the Renaissance room, as Henriette had decorated it (MMB.F.408)

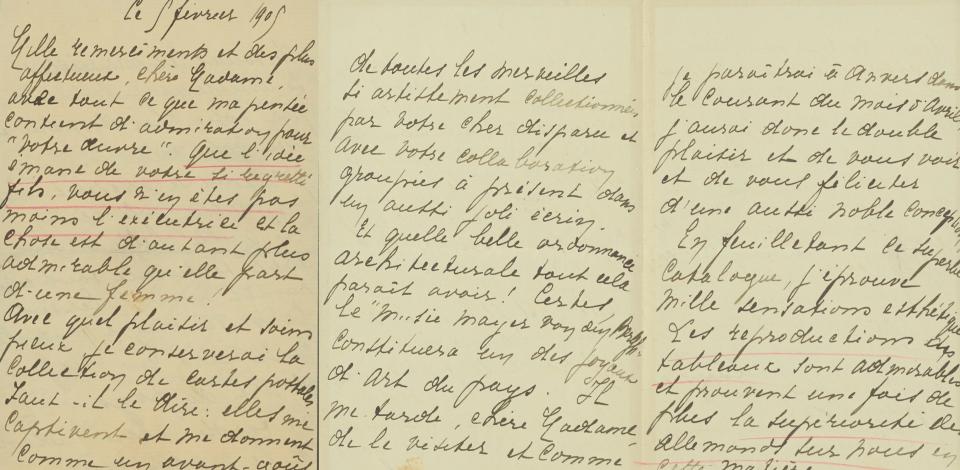

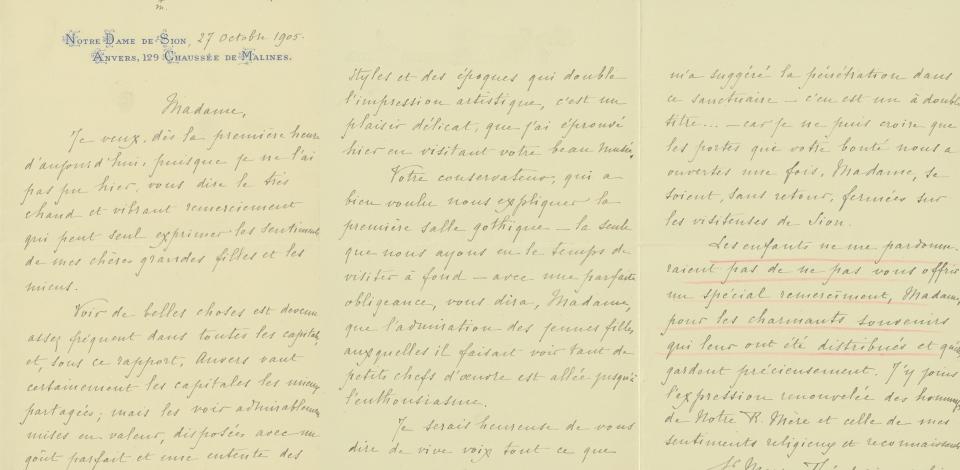

Letter from Marie Théodorine de Sion to Henriette van den Bergh about her museum visit, 27-10-1905 (MMB.A.2347).

Henriette emphatically presented herself as the executor of Fritz's ideas. This also legitimised the public position she assumed as a woman after founding her own museum and was also highly appreciated by museum visitors. One visitor, for example, wrote that in the museum "a motherly love” was palpable that “respects [Fritz's] work down to the smallest detail."

Yet Henriette also contributed her own vision. The Museum Mayer van den Bergh fits in the tradition of the female collector's museum, with its characteristic intimacy and domestic atmosphere. It was also located next to Henriette's own home, and most guests were led through her interior before entering the museum. "A very intimate visit," wrote one visitor. Another described his tour of the museum as "coming home."

In a sense, this also makes the museum a continuation of the private interiors that Henriette had been working on for much longer. She determined how art works were displayed in the museum, where they were placed, and what atmosphere was evoked in the various rooms. She even removed one of the works from Fritz's collection - a painting of a drunken woman by Jan Steen - from the collection, finding it inappropriate.

Henriette Mayer van den Bergh, early 20th century, photo, Museum Mayer van den Bergh Archives (MMB.F.017).

A model for other museums

Louise de Hem's letter shows that in 1904 people were well aware of what it meant to be a female museum founder. Henriette founded the museum to keep her son's memory alive, but the museum was also her own project. She determined the presentation of the artworks and the intimate atmosphere that we still see in the rooms today, with her taste and vision. Although the exact layout of the museum has changed considerably, Henriette's vision has been preserved to this day. Moreover, after the foundation of the museum, Henriette became a public figure in the Antwerp art world - a position that few women managed to attain. Clearly, as a museum founder, she was highly regarded, by both men and by women. The well-known Belgian writer and museum curator Pol De Mont wrote to her, "Not only collectors, but even museum curators can learn from you how to deal with works of art from the past."