Own entourage

Some of the showpieces in his collection – including Mad Meg (also known as 'Dull Gret') – came into Fritz's possession through the use of intermediaries or agents. Among other things, they kept him informed of upcoming auctions at home and abroad. (Art magazines also reported on future auctions, and loyal customers were sent catalogues by auction houses.)

Such an intermediary attended the auction in Fritz's place, after thorough instructions on which pieces were highest on his wish list and the maximum amount he was willing to pay for them. His archives and purchase ledger show that, over the years, he enlisted dozens of people as intermediaries, from Paris to Stockholm, from Berlin to Florence. In return, they asked for a commission of 5 to 10 percent of the artwork's price. They also took care of all the formalities for having the artwork transported to Antwerp.

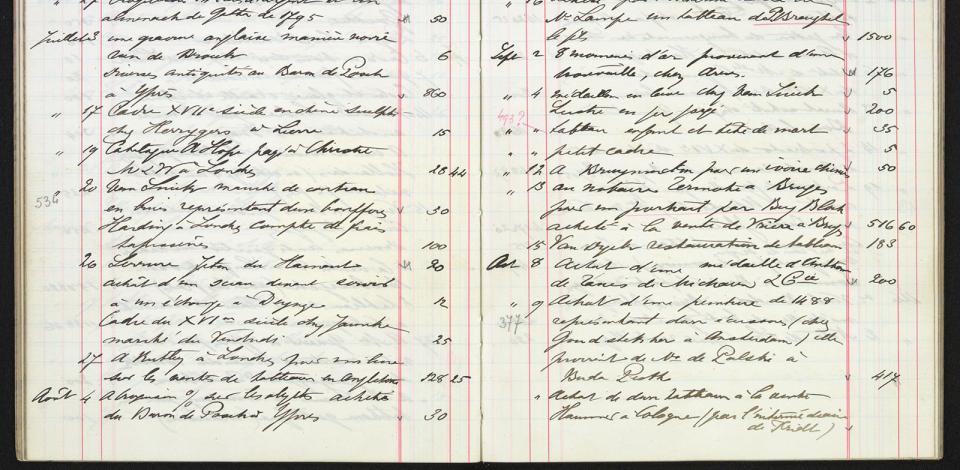

The purchase of 'Mad Meg' 'by the intermediary of Fridt' in Fritz's book of purchases, 9-10-1894.

The easiest way to find an intermediary was to look for antique dealers in the city of the auction. They earned a pretty penny from such services. However, many collectors were quite reluctant to involve art dealers in a purchase because they were competitors rather than colleagues, and because they were out for profit. So with most antique dealer intermediaries, Fritz kept it to one partnership. Most often, he enlisted people from his own entourage as agents, such as the conservators who worked for him. They knew his taste like no other and had already gone to great lengths to prove their loyalty to Fritz. Joseph Delehaye, for example, whom he had regularly consulted since 1890 for having paintings restored, went to Italy in 1891 to manage the purchase of the triptych Adoration of the Magi. In 1899, Juvenal Peellaert, the conservator whom Fritz had permanently employed for a year at the time, travelled to Spain and Portugal to negotiate for some artworks there.

Most expensive purchase ever

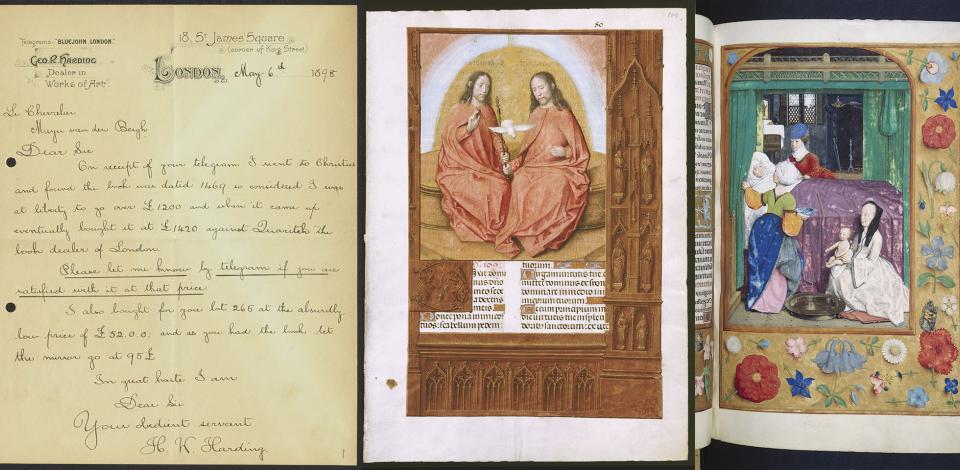

For other purchases abroad, Fritz did do business with intermediaries he may never have met in person. In this, he remained selective. His network of agents largely overlapped with the circles of art experts from whom he sought advice. He got to know one of his most loyal agents in London, the silver and enamel dealer George Robinson Harding, thanks to a tip-off from Heinrich Angst, later the Director of the Schweizerisches Landesmuseum in Zurich, with whom he discussed his purchases in numerous letters. That connection later provided Fritz with one of the masterpieces in his collection: Harding bought the late-15th-century Breviary for him at the Martin Heckscher estate auction at Christie's. Although Fritz had set the limit of his maximum budget at 1,200 pounds, Harding continued to bid higher at his own initiative, going as high as 1,420 pounds (35,500 francs). That made this manuscript Fritz's most expensive purchase ever. Harding made this impulsive decision when he noticed that Bernard Quaritch, a competing antique dealer and renowned manuscript expert, was bidding higher and higher. This incident shows that intermediaries bore an enormous responsibility: they had to be able to assess the quality of the work in-situ and know their competitors, as well as to be able to react smoothly to unexpected twists and turns during the sale.

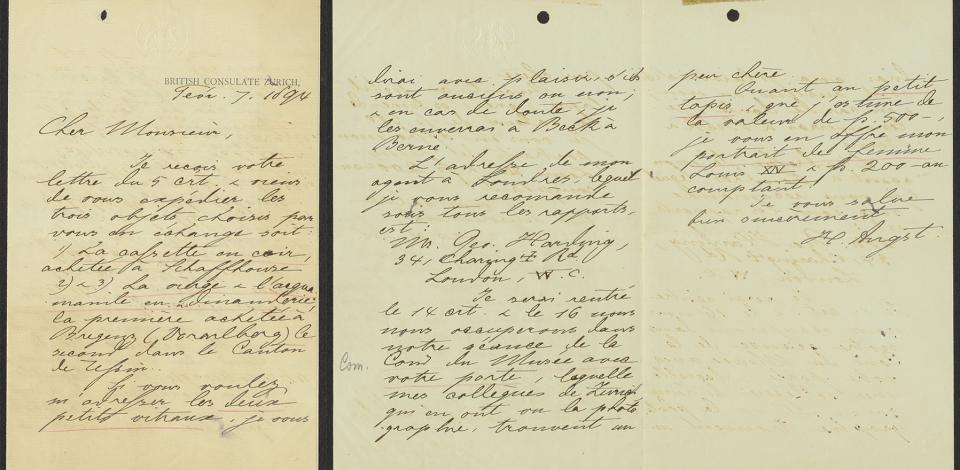

'The address of my agent in London, who I would recommend to you in all respects, is Mr Geo. Harding, 34, Charing † Rd. London.’ Letter from Heinrich Angst to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh, 7-02-1894, MMB.A.0412.

Letter from George Robinson Harding to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh, 6-05-1898, MMB.A.0852. / Mayer van den Bergh Breviary, MMB.0618, fol. 100 front and fol. 536 back.

Informants

Closer to home, Fritz himself did usually attend auctions in person. Yet he maintained an equally extensive network of intermediaries in every region of Belgium and the Netherlands. On the one hand, these contacts were necessary for informally tracking down interesting artworks beyond the circuit of 'official' auctions and antique dealers, for example when the owners were concerned about their privacy. Fritz's informants notified him by letter when influential collectors of their acquaintance died or when people needed to dispose of part of their collection due to money problems. On the other, Fritz brought in an agent when he expected a lot of headwinds from the seller and their entourage, in order to be stronger together in negotiations.

First aid in negotiations

A good example of the latter is the help Fritz received from Utrecht illustrator Jan Bos, when he acquired eighteen paintings from the family estate of François Bredehoff of Oosthuizen in 1897. Six portraits hung in Utrecht's Gebouw voor Kunsten en Wetenschappen ('Arts and Sciences Building'), the headquarters of the cultural society Kunstliefde ('Love of Art'), which Bos and Bredehoff may both have frequented. It was only possible to remove the works of art from there with an 'accompanying letter' to the board of the association. Another set was in the private home of François' sister, who did not yet feel ready to dispose of the pieces, as their mother had died less than a year earlier. That tense situation did not stop Bos from playing the game of negotiation very hard: he still tried to convince Bredehoff that the family portrait of Meyndert Sonck and his family by Jan Albertsz. Rotius 'could be a copy', perhaps to make it easier to get hold of. In sales issues such as this one, in which many parties had a voice, Fritz might never have been able to reach a successful conclusion without the help of a mediator who was at home in the seller's circles.

Jan Albertsz. Rotius, "Meyndert Sonck and his family," 1662, MMB.0138.

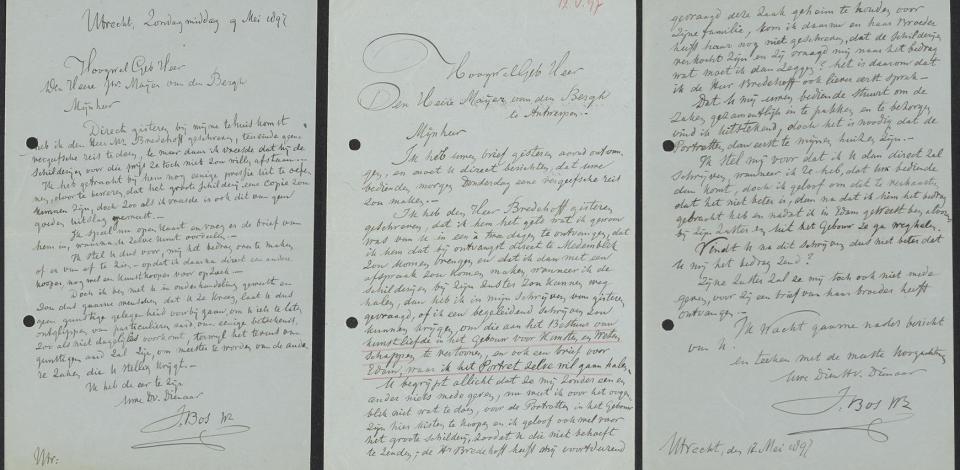

1. 'I have tried to exert some pressure upon him by claiming that the large painting could be a copy, but as I feared, this too has been of no avail.' Letter from Jan Bos to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh, 9-05-1897, MMB.A.0765.

2. 'I wrote to Mr Bredehoff yesterday [...] whether I could get an accompanying letter, to show it to the Art-Lovers' Board at the Building for Arts and Sciences.' Letter from Jan Bos to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh, 12-05-1897, MMB.A.0767.

Question marks

Such letters show that Fritz Mayer van den Bergh's archives not only provide an insight into the story behind each artwork, but also question the romanticised image of the art collector as a 'lone genius'. Beyond a 'treasure hunt' across Europe, his collecting practice was primarily a matter of strategic collaboration with a vast network of helping hands, which he carefully built and coordinated. Fritz was richly rewarded for those efforts, including with some outstanding works.