Selective

Owing to the enormous diversity within Fritz's collection – from sculptures to textiles, paper to porcelain – it was no easy task to give each work the proper treatment. Numerous invoices and letters in his archives show that he called upon ten studios, each with their own expertise, for his restoration jobs. In Fritz's eyes, restoring paintings was a complex and multifaceted task that was best left to specialists. For problems with the canvas or panel – that is, not with the paint layer itself – he consistently called upon the services of Antoine Sacré, who also worked regularly for the Antwerp Museum of Fine Arts, beginning in 1892. Sacré was Fritz's regular craftsman for, among other things, 'lining' a painting (gluing a second canvas to reinforce the whole) and 'cradling' panels (attaching a grid of wooden slats under the panel). For the finer work in the paint and varnish layers, he worked with several conservators. In doing so, Fritz remained selective and gave absolute priority to his 'masterpieces'. Sacré's accounts show that the collector cared most for his paintings by the Bruegel dynasty and 17th-century Dutch masters, especially the portraits. For example, a late-17th-century portrait by Jan van Haensbergen (then attributed to Caspar Netscher) was lined twice in less than a year.

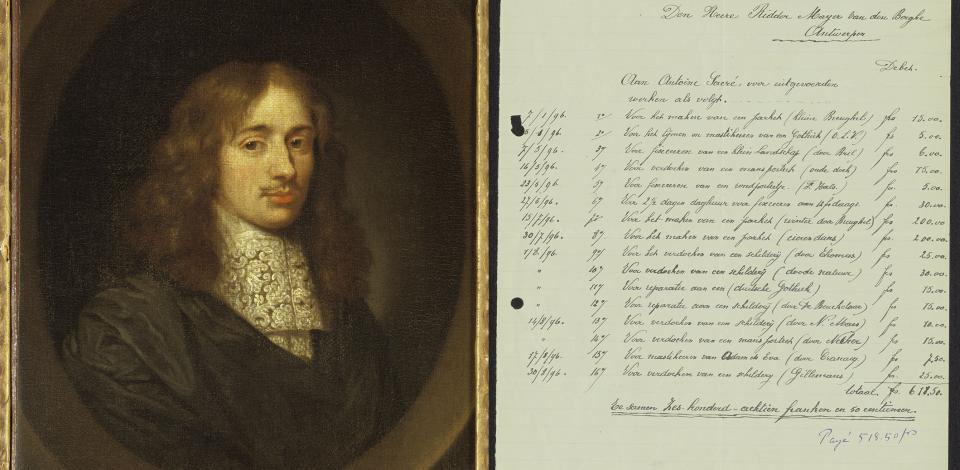

Jan van Haensbergen, 'Portrait of Anthony Verlaan'(?), 1675-1699, MMB.0159. / Invoice for the lining of, among other things, this portrait (Antoine Sacré to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh, 25-09-1896, MMB.A.0690).

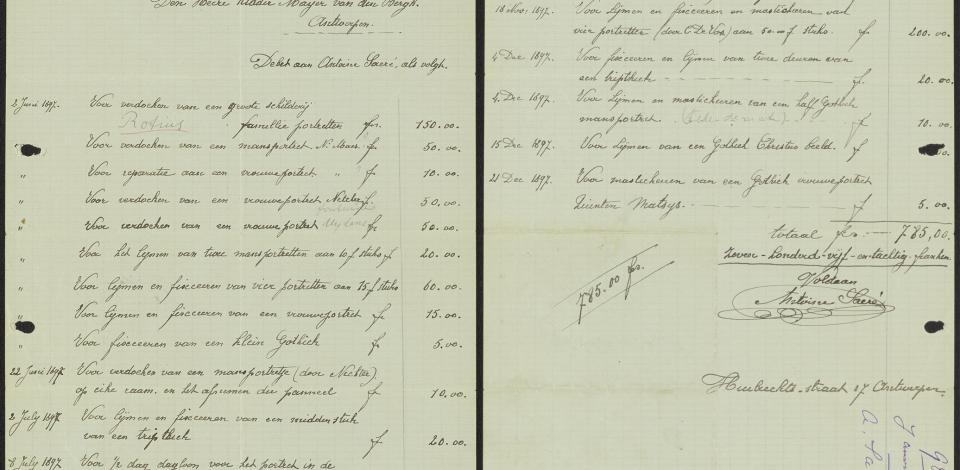

Invoice for a series of restorations from January through December 1897, including for the 'lining of a man's portrait by Nechter [sic] on an oaken frame and taking off the panel' (Antoine Sacré to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh, 10-01-1898, MMB.A.0618).

To Berlin!

Some objects needed such specific care that Fritz sought conservators outside of Antwerp. For tapestries, for example, he chose renowned craftsmen with the tapestry studios Braquenié, Leopold II's court suppliers, and with the Brussels-based Arthur Lambrechts. Once, he even went to a speciality store in Paris with a fan – a gift for Henriëtte.

However, the bar seemed highest for the restoration of the portrait of Francesco de' Medici. Shortly after the purchase, Fritz had already rejected one prospective conservator because he was only moderately convinced of his approach. However, continuing to delay was no longer possible when a hole appeared in the canvas – probably during transport to Belgium six months later. Because that damage had affected both the support and the paint layer, Fritz thought his regular Antwerp conservators might be too specialist to judge the overall picture and turned to Berlin's Royal Museums. He had the work shipped to Berlin to be restored by Alois Hauser, the museum's permanent conservator. Hauser waited six months to begin the restoration, but showed a great willingness to tackle the work in accordance with Fritz's requirements. There was only one non-negotiable condition: to determine the correct colour for the fragment he would reconstruct, he had to remove part of the varnish layer.

'I sent the painting itself to Mr Hauser because there was a small hole in it and I wrote that you might come and see it.' Letter from Fritz Mayer van den Bergh to Wilhelm von Bode, 4-01-1894. Berlin, Zentralarchiv, Staatliche Museen – Preußischer Kulturbesitz.

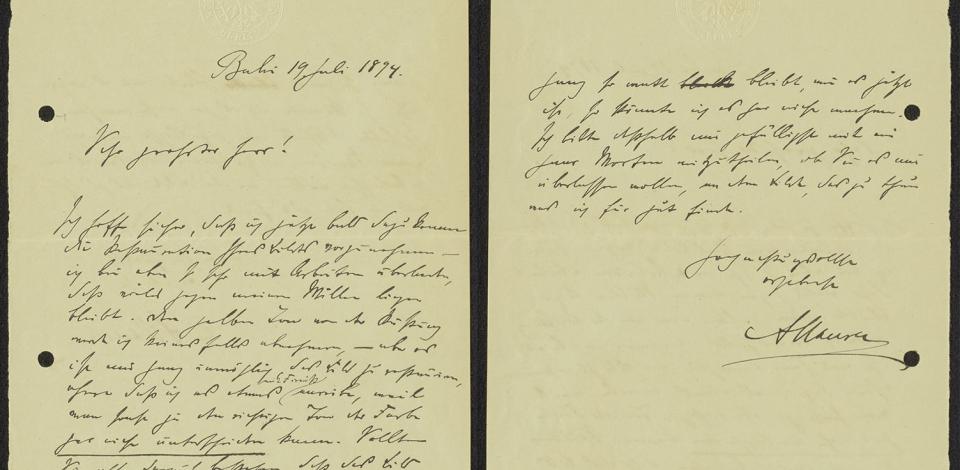

'It is quite impossible for me to restore the painting without rubbing it with some varnish, because otherwise you wouldn't be able to tell the right tone of the paint at all.' Letter from Alois Hauser to Fritz Mayer van den Bergh, 19-07-1894, MMB.A.0476.

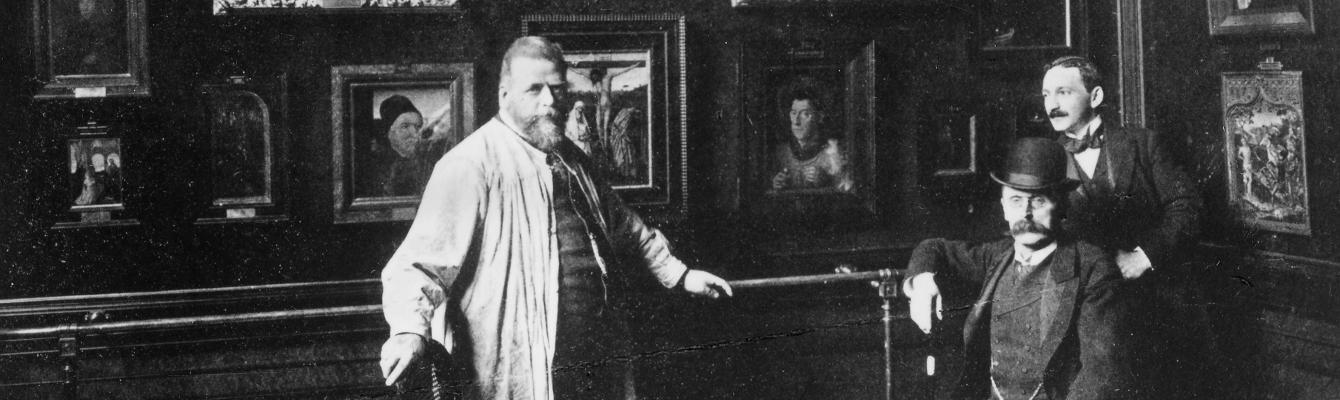

Alois Hauser, Wilhelm von Bode and Max Friedländer at the Kaiser Friedrich Museum, ca. 1900. Berlin, SMB-ZA, V/Fotosammlung ZA 2.4./04772. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Demanding customer

Some sources characterise Fritz as a demanding customer who insisted upon a great deal of participation in the restoration process. He outsourced important commissions only after consulting several studios, and according to his purchase ledger, he paid an advance to some for a 'trial restoration'. In 1893, Fritz knocked on Arthur Lambrechts' door for some repairs to a small Brussels Gothic tapestry depicting the birth of Jesus – one of the few tapestries Fritz did not resell. In his contract, Lambrechts seemed to realise that Fritz was setting the bar high: he let Fritz choose silk and wool himself and had the commission executed by his best colleague, Marie Verdonck, who later in her own studio produced carpets for the Arenberg family, among others. Also, hardly any dyes would be used in the treatment, to keep the authenticity of the work as intact as possible.

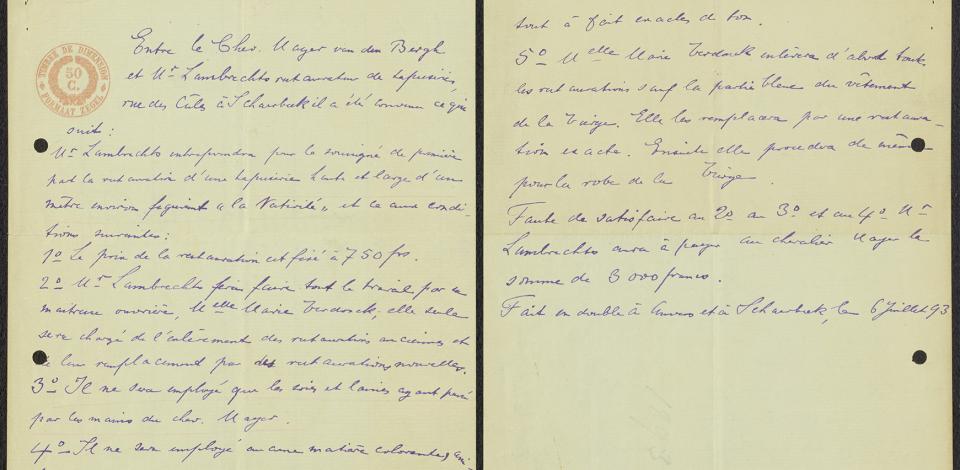

Contract between Arthur Lambrechts and Fritz Mayer van den Bergh, 6-07-1893, MMB.A.1665.

Anonymous, 'Birth of Jesus', ca. 1500, MMB.0954.

Art restorer Mayer van den Bergh?

Fritz's extraordinary interest in the conservation of his artworks went even further: one letter shows that he occasionally went to work himself as an amateur conservator. In 1891, he made plans to exchange some works of art with Heinrich Angst, later the Director of the Schweizerisches Landesmuseum in Zurich. He tried to convince Angst to give him another 17th-century French female portrait as a bonus in addition to the pieces agreed upon, because he wanted to remove all previous retouching of the work, and 'restore it better if possible' (l'arranger mieux si possible'). There is no trace of the portrait – it is even doubtful that the exchange ultimately went through – and in no other archival source does Fritz mention his own DIY restorations. Did he deliberately remain discreet about it, because public opinion could be very harsh about the danger of amateur restorations? In any case, his modest tone suggests that he knew his place in respect of his professional colleagues, as he deliberately selected a work of moderate quality: 'It is not that I think it valuable, but it would amuse me to restore it.'

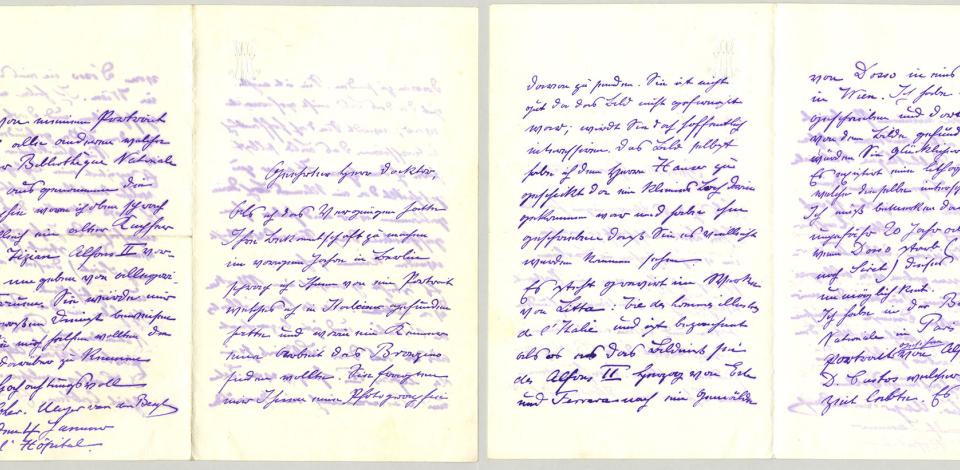

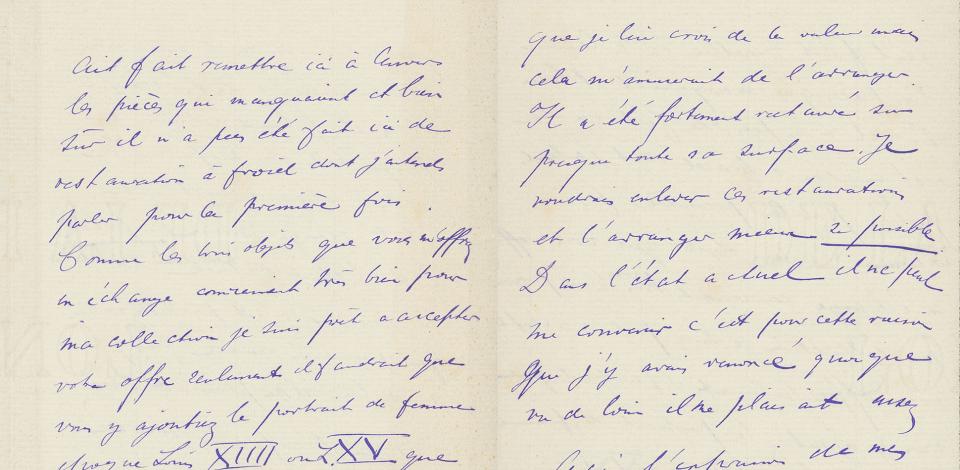

Fritz Mayer van den Bergh to Heinrich Angst, s.d. (November 1891?), Zurich, Zentralbibliothek, Nachl. H. Angst 58.62.

A permanent conservator

After 1898, Fritz traded in his loose partnerships with various studios for a single permanent conservator, the Brussels-based Juvenal Peellaert. After Fritz's death, Henriëtte promoted him to museum curator, with an annual salary of 10,000 francs. He was given his own studio space in the building, called simply the 'studio', which was also part of the museum trail. Henriëtte kept a close eye on Peellaert's restoration work. When, in her opinion, he spent too much time on one work of art, she reported it in a letter to her notary Alphonse Cols. When Peellaert began using his studio for private restoration jobs that had nothing to do with the museum, she also said this violated their contract.

Although Henriëtte left everything to a single conservator, she also continued her son's life's work in her vision for restoration. Both son and mother showed themselves to be commited clients with a critical spirit. They recognised conservators as fully-fledged art experts and immersed themselves in the craft, but for the ultimate implementation, they still had the final say.

Peellaert restoration studio, early 20th century, MMB.F.192.

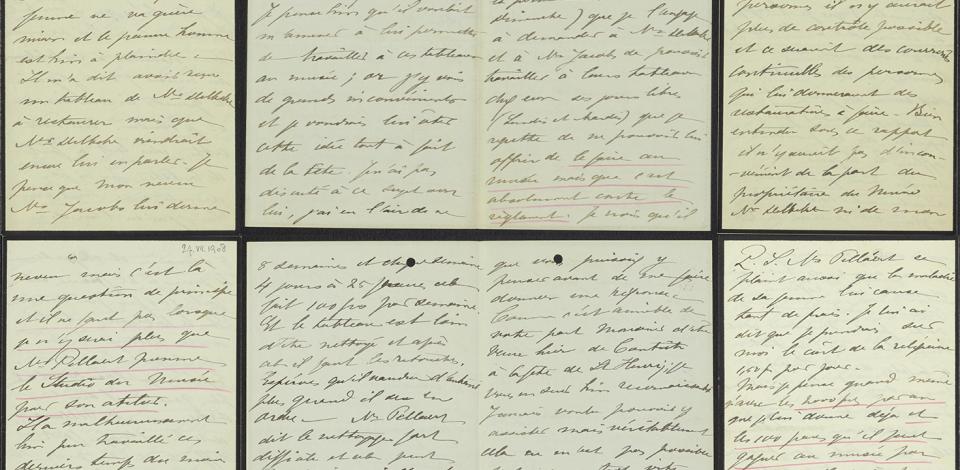

'If I were to allow him (sc. Juvenal Peellaert) to restore other people's paintings at the museum, it would get out of hand and there would be continual requests from people giving him their restorations to do.' Henriette Mayer van den Bergh to Alphonse Cols, 27-07-1908, MMB.A.1638.